An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) indicate that the job openings level and rate continued to grow during 2012. On an annual basis, data that are not seasonally adjusted show that the average monthly number of job openings increased from 3.2 million in 2011 to 3.6 million in 2012. The average monthly job openings rate rose from 2.3 percent to 2.6 percent. The increases in average monthly hires and separations, however, were not as large. From 2011 to 2012, the average monthly number of hires ticked up from 4.1 million to 4.3 million while the rate held steady at 3.2 percent. Besides illustrating the preceding data, the following tabulation shows that the average monthly number of separations increased from 4.0 million in 2011 to 4.1 million in 2012 while the average monthly rate rose from 3.0 percent to 3.1 percent between the 2 years (data not seasonally adjusted):

| Number (thousands) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Category | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

Job openings | 2,848 | 3,151 | 3,632 |

Hires | 4,051 | 4,140 | 4,333 |

Separations | 3,971 | 3,969 | 4,140 |

| Rate (percent) | |||

Category | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

Job openings | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

Hires | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

Separations | 3 | 3 | 3.1 |

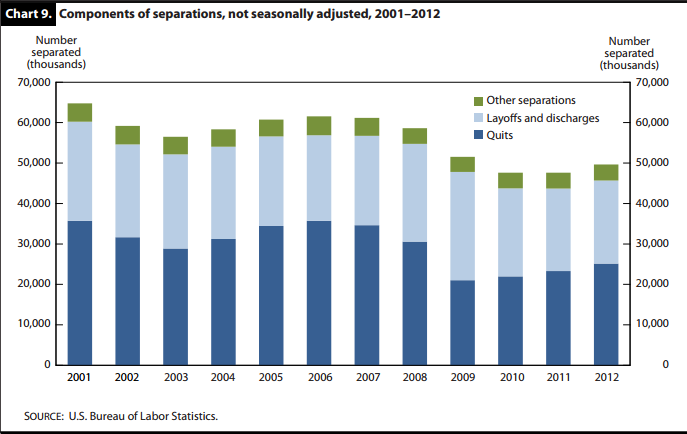

JOLTS breaks down separations into quits, layoffs and discharges, and other separations. In 2012, quits contributed the most to the increase in separations. The average monthly number of quits increased from 1.9 million in 2011 to 2.1 million in 2012. The average monthly number of layoffs and discharges remained stable at 1.7 million between the 2 years.

JOLTS data provide measures of job openings, hires, total separations, quits, layoffs and discharges, and other separations on a monthly basis by industry1 and geographic region.2 JOLTS gauges labor demand and worker flows by collecting data from a sample of approximately 16,400 nonfarm business establishments. This article reviews changes in the estimates generated by the JOLTS measures over 2012, as well as how these measures have fared since the most recent recession. To do so, 2012 JOLTS data are compared with previous years’ JOLTS data as well as other statistical series. JOLTS data are available beginning December 2000. In what follows, monthly averages or annual totals, neither of which are seasonally adjusted, are presented. Data for a specific month (e.g., December 2012) or quarter (e.g., the second quarter of 2012) are seasonally adjusted.

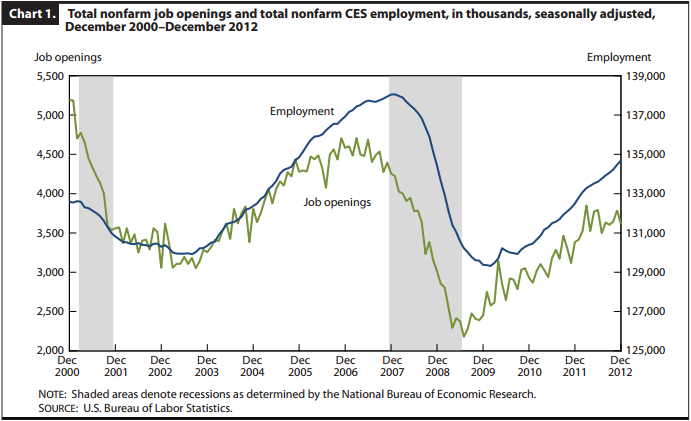

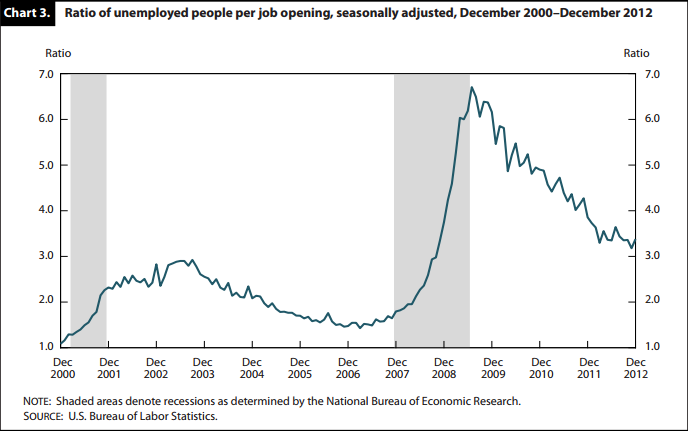

Job openings—the number of openings on the last business day of the reference month—are a procyclical measure of the demand side of the labor market. That is to say, during an economic contraction employers tend to demand less labor, reducing the number of job openings they have or shedding them entirely. As labor demand decreases, employment also tends to decrease. By contrast, during an economic expansion employers tend to demand more labor, increasing the number of job openings they have. As labor demand rises, employment tends to rise. All in all, then, job openings and the Current Employment Statistics (CES)3 nonfarm payroll employment estimates tend to have similar growth trends.4 (See chart 1.)

In 2012, as well as in 2011, the total number of nonfarm job openings and nonfarm payroll employment tracked consistently. On an annual basis, the average monthly number of job openings increased 15.3 percent in 2012, from 3.2 million to 3.6 million. By way of comparison, in 2011 the average monthly number of job openings grew 10.6 percent. Similarly, nonfarm payroll employment showed a positive, increasing percentage of growth for both years. In 2012, average monthly CES employment rose by 1.7 percent over the 2011 figure. The increase in 2011 was 1.2 percent. (See table 1.)

| Year | Average monthly number of job openings | Percent change from previous year | Average monthly CES employment | Percent change from previous year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2001 | 4,287 | (1) | 131,919 | 0.0 |

2002 | 3,414 | –20.4 | 130,450 | –1.1 |

2003 | 3,211 | –5.9 | 130,100 | –.3 |

2004 | 3,580 | 11.5 | 131,509 | 1.1 |

2005 | 4,058 | 13.4 | 133,747 | 1.7 |

2006 | 4,428 | 9.1 | 136,125 | 1.8 |

2007 | 4,484 | 1.3 | 137,645 | 1.1 |

2008 | 3,694 | –17.6 | 136,852 | –.6 |

2009 | 2,451 | –33.7 | 130,876 | –4.4 |

2010 | 2,848 | 16.2 | 129,917 | –.7 |

2011 | 3,151 | 10.6 | 131,497 | 1.2 |

2012 | 3,632 | 15.3 | 133,739 | 1.7 |

Notes: (1) The JOLTS program did not begin until 2001, so there are no data for the previous year.Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||

On a quarterly basis, in 2012 the number of job openings was up 10.0 percent in the first quarter, up 2.8 percent in the second quarter, down 3.2 percent in the third quarter, and up 2.9 percent in the final quarter. The low for the year was 3.4 million, in January, the high 3.8 million, in March.

Following the recession,5 total nonfarm job openings trended upward, from 2.4 million in June 2009 to 3.6 million in December 2012. The number of openings still has not reached the 4.3 million level at which it stood at the beginning of the recession, in December 2007.

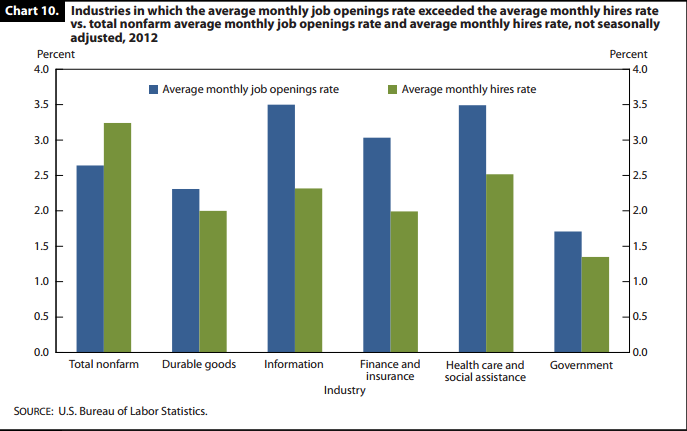

Job openings by industry and region. On an annual basis, the total nonfarm average monthly job openings rate rose from 2.3 percent in 2011 to 2.6 percent in 2012. Real estate and rental and leasing saw the largest percent increase in the average monthly job openings rate, a 33.3-percent rise, from 2.1 percent to 2.8 percent over the year. Next was nondurable goods manufacturing, which grew 31.3 percent, from 1.6 percent to 2.1 percent. The rate declined the most in mining and logging, which posted a 39.4-percent drop over the year, from 3.3 percent to 2.0 percent. Information was next, falling 7.9 percent, from 3.8 percent to 3.5 percent. Table 2 shows the average monthly number of job openings and the average rate of job openings, by industry, for 2011 and 2012.

| Industry | Number (thousands) | Rate (percent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | |

Total | 3,151 | 3,632 | 481 | 15.3 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 13.0 |

Total private | 2,821 | 3,251 | 430 | 15.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | .3 | 12.0 |

Mining and logging | 26 | 18 | –8 | –3.8 | 3.3 | 2.0 | –1.3 | –39.4 |

Construction | 75 | 81 | 6 | 8.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | .1 | 7.7 |

Manufacturing | 227 | 271 | 44 | 19.4 | 1.9 | 2.2 | .3 | 15.8 |

Durable goods | 157 | 176 | 19 | 12.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | .2 | 9.5 |

Nondurable goods | 71 | 95 | 24 | 33.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 | .5 | 31.3 |

Trade, transportation, and utilities | 540 | 615 | 75 | 13.9 | 2.1 | 2.4 | .3 | 14.3 |

Wholesale trade | 112 | 131 | 19 | 17.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | .3 | 15.0 |

Retail trade | 316 | 371 | 55 | 17.4 | 2.1 | 2.4 | .3 | 14.3 |

Transportation, warehousing, and utilities | 112 | 113 | 1 | .9 | 2.3 | 2.2 | –.1 | –4.3 |

Information | 104 | 97 | –7 | –6.7 | 3.8 | 3.5 | –.3 | –7.9 |

Financial activities | 203 | 240 | 37 | 18.2 | 2.6 | 3.0 | .4 | 15.4 |

Finance and insurance | 162 | 183 | 21 | 13.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | .3 | 11.1 |

Real estate and rental and leasing | 41 | 57 | 16 | 39.0 | 2.1 | 2.8 | .7 | 33.3 |

Professional and business services | 589 | 676 | 87 | 14.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 | .3 | 9.1 |

Education and health services | 575 | 676 | 101 | 17.6 | 2.8 | 3.2 | .4 | 14.3 |

Educational services | 62 | 62 | 0 | .0 | 1.9 | 1.8 | –.1 | –5.3 |

Health care and social assistance | 513 | 613 | 100 | 19.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | .5 | 16.7 |

Leisure and hospitality | 362 | 438 | 76 | 21.0 | 2.6 | 3.1 | .5 | 19.2 |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 46 | 55 | 9 | 19.6 | 2.3 | 2.7 | .4 | 17.4 |

Accommodations and food services | 316 | 383 | 67 | 21.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | .5 | 18.5 |

Other services | 119 | 140 | 21 | 17.6 | 2.2 | 2.5 | .3 | 13.6 |

Government | 330 | 381 | 51 | 15.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | .2 | 13.3 |

Federal | 53 | 66 | 13 | 24.5 | 1.8 | 2.3 | .5 | 27.8 |

State and local | 277 | 314 | 37 | 13.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | .2 | 14.3 |

Notes: (1) The average number of monthly job openings is the average number of job openings on the last business day of each month during the year. | ||||||||

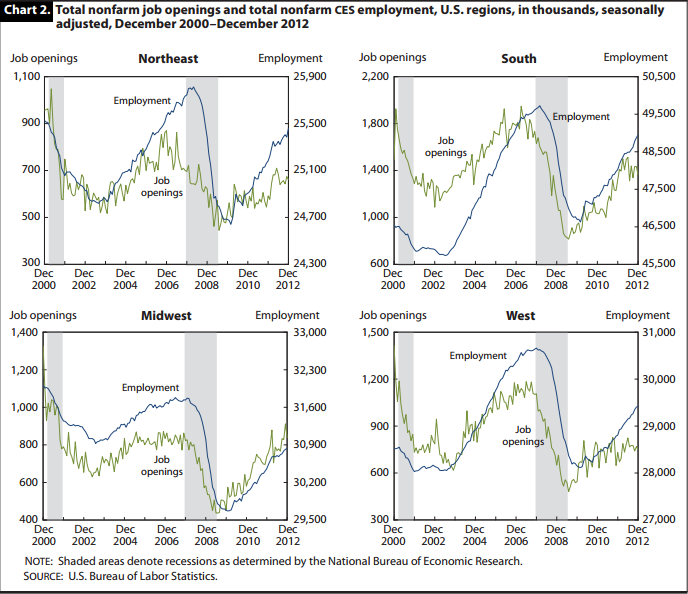

| Job openings | Northeast | South | Midwest | West | ||

| Number (thousands): | ||||||

| 2011 | 574 | 1,144 | 697 | 736 | ||

| 2012 | 658 | 1,417 | 801 | 756 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | 84 | 273 | 104 | 20 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | 14.6 | 23.9 | 14.9 | 2.7 | ||

| Rate (percent): | ||||||

| 2011 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | ||

| 2012 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | .2 | .5 | .3 | .0 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | 8.7 | 21.7 | 13.0 | .0 |

Definitions of JOLTS terms

Job openings are the number of openings on the last business day of the reference month.

Hires are all additions of personnel to the payroll during the reference month.

Total separations are the number of employees separated from payroll during the reference month.

Quits are separations in which employees left a job voluntarily but did not retire or transfer.

Layoffs and discharges are involuntary separations initiated by employers.

Other separations are separations due to retirement, transfers, or deaths and separations caused by disability.

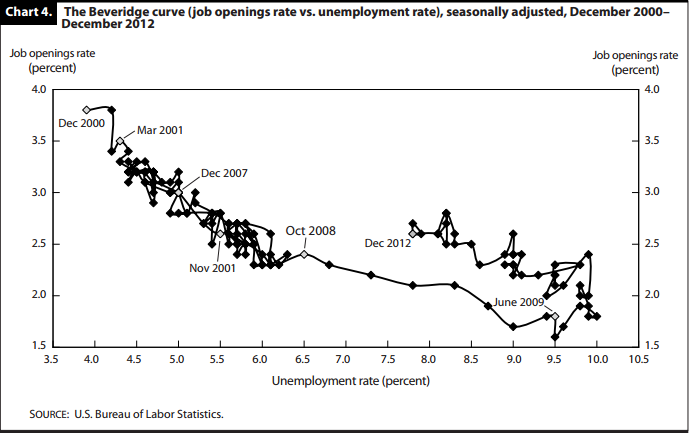

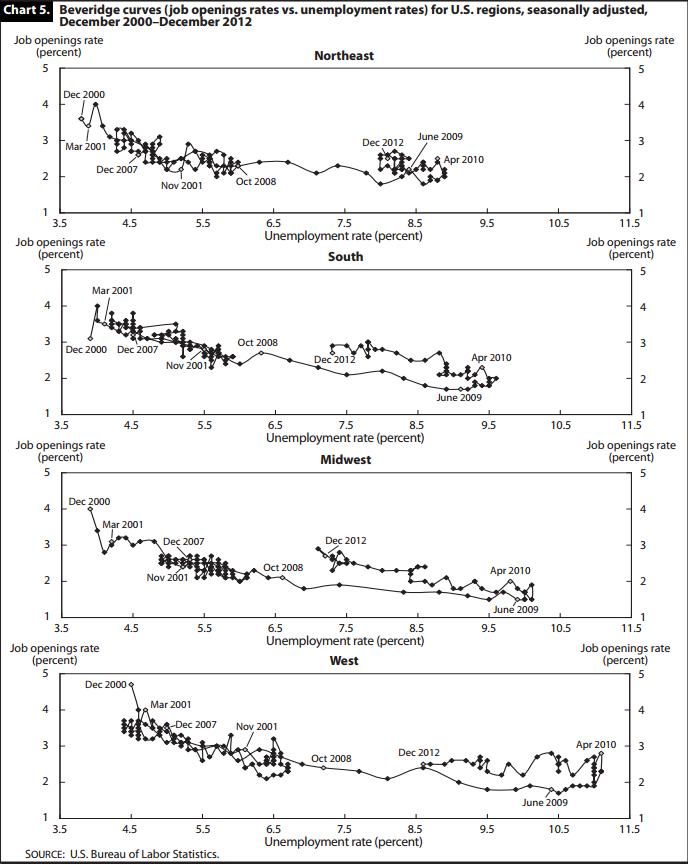

Beveridge curves also can be calculated for the four regions, with the use of JOLTS and Local Area Unemployment Statistics data.9 In 2012, the Beveridge curve for the Northeast moved upward and slightly to the right as the job openings rate rose from 2.2 percent in January to 2.5 percent in December while the unemployment rate grew from 8.0 percent in January to 8.1 percent in December. The Beveridge curve for the South moved slightly downward and to the left, with the job openings rate dropping from 2.8 percent in January to 2.7 percent in December and the unemployment rate falling from 8.0 percent in January to 7.3 percent in December. The Beveridge curve for the Midwest moved upward and to the left as the job openings rate increased from 2.5 percent in January to 2.7 percent in December while the unemployment rate fell from 7.6 percent in January to 7.2 percent in December. The Beveridge curve for the West moved up and to the left, with the job openings rate rising from 2.2 percent in January to 2.5 percent in December while the unemployment rate dropped from 9.7 percent in January to 8.6 percent in December.

In the first half of 2010, all of the regional Beveridge curves shifted outward, as did the national curve; however, they all shifted in various ways and degrees and continued to develop differently during the recovery. (See chart 5.) In the Midwest, although the initial shift in the curve was not as large as that in the other regions, by 2012 the curve had moved farther out on the grid. By contrast, the West experienced a large initial shift in its curve, but in 2012 the curve moved closer to its 2010 location, exhibiting an increase in job-matching efficiency.

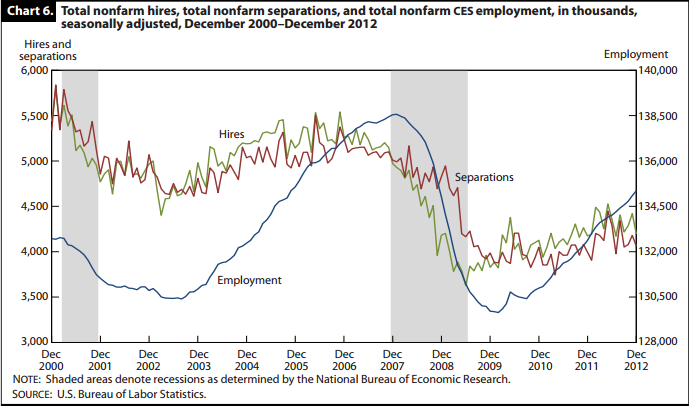

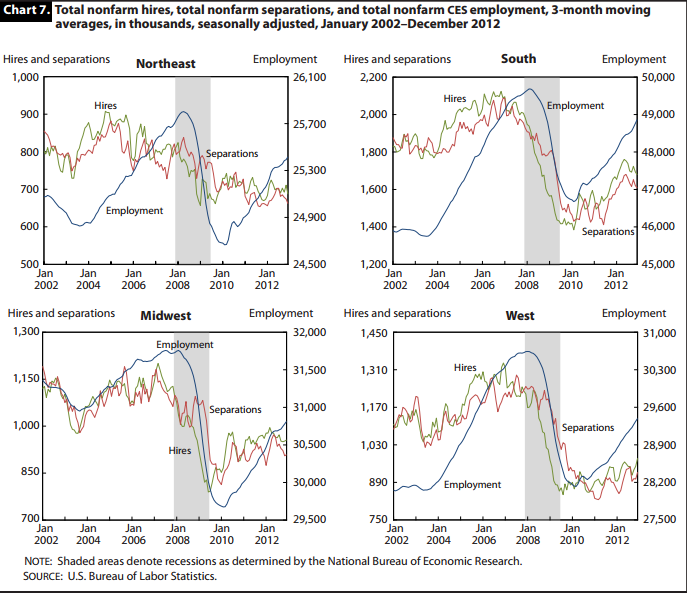

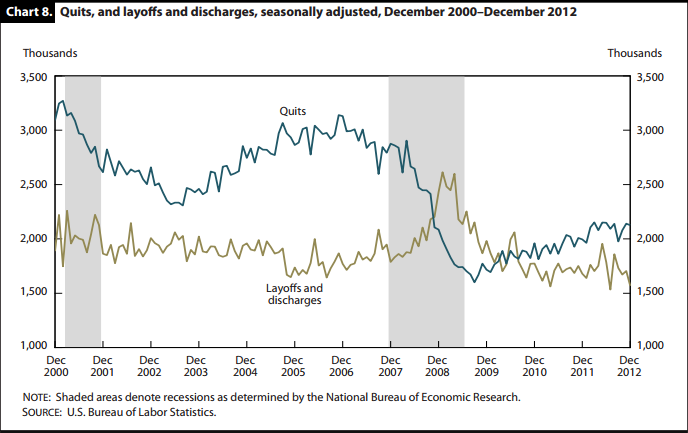

Hires, along with separations, demonstrate another important aspect of the labor market: worker flow. (See charts 6 and 7.) The number of hires is a procyclical measure, rising during an expansion and falling during a recession. The separations measure is more complex. There are three elements within separations: quits, layoffs and discharges, and other separations. Quits, which are voluntary separations, are a procyclical measure; layoffs and discharges, which are involuntary separations, constitute a countercyclical measure. That is, during an expansion, more people quit their jobs and fewer people are laid off. During a recession, more people are laid off and fewer people quit their jobs. These two elements countering each other, but with quits usually predominating, make separations overall a mildly procyclical measure.10 (See chart 8.) The last element within separations, other separations—which include separations due to retirement, death, and disability, as well as transfers to other locations of the same firm—tends to be procyclical. However, because of its smaller size relative to the other two components of separations, the category of other separations tends not to have a large impact on total separations. (See chart 9.)

| Year | Number of hires | Percent change from previous year | Annual hires rate |

|---|---|---|---|

2001 | 62,948 | (1) | 47.8 |

2002 | 58,583 | –6.9 | 44.9 |

2003 | 56,451 | –3.6 | 43.4 |

2004 | 60,367 | 6.9 | 45.9 |

2005 | 63,150 | 4.6 | 47.2 |

2006 | 63,773 | 1.0 | 46.9 |

2007 | 62,421 | –2.1 | 45.4 |

2008 | 55,128 | –11.7 | 40.3 |

2009 | 46,357 | –15.9 | 35.4 |

2010 | 48,607 | 4.9 | 37.4 |

2011 | 49,675 | 2.2 | 37.8 |

2012 | 51,991 | 4.7 | 38.9 |

Notes: (1) The JOLTS program did not begin until 2001, so there are no data for the previous year. | |||

Since the end of the recession, the number of hires has been trending upward, from 3.6 million in June 2009 to 4.2 million in December 2012. The number has yet to rise to the 5.0 million level at which it stood at the beginning of the recession, in December 2007.

1. Hires by industry and region. Table 4 gives the annual number of hires and the annual rate of hiring, by industry, for 2011 and 2012. Most industries experienced an increase in their annual hires rate from 2011 to 2012. The total nonfarm annual hires rate rose from 37.8 percent in 2011 to 38.9 percent in 2012. The industries with the greatest percent decreases in their annual hires rate were educational services, which fell 8.6 percent, from 29.0 percent in 2011 to 26.5 percent in 2012, and nondurable goods, which dropped by 7.4 percent, from 28.4 percent in 2011 to 26.3 percent in 2012. The industries with the greatest increases in their annual hires rate were finance and insurance, which grew by 17.1 percent, from 20.5 percent in 2011 to 24.0 percent in 2012, and financial activities, which rose 14.1 percent, from 24.1 percent in 2011 to 27.5 percent in 2012.

| Industry | Number (thousands) | Rate (percent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | |

Total | 49,675 | 51,991 | 2,316 | 4.7 | 37.8 | 38.9 | 1.1 | 2.9 |

Total private | 46,552 | 48,493 | 1,941 | 4.2 | 42.5 | 43.4 | .9 | 2.1 |

Mining and logging | 335 | 380.0 | 45 | 13.4 | 42.5 | 44.7 | 2.2 | 5.2 |

Construction | 4,098 | 3,900 | –198 | –4.8 | 74.1 | 69.1 | –5.0 | –6.7 |

Manufacturing | 3,035 | 2,967 | –68 | –2.2 | 25.9 | 24.9 | –1.0 | –3.9 |

Durable goods | 1,771 | 1,794 | 23 | 1.3 | 24.4 | 24.0 | –.4 | –1.6 |

Nondurable goods | 1,263 | 1,174 | –89 | –7.0 | 28.4 | 26.3 | –2.1 | –7.4 |

Trade, transportation, and utilities | 9,946 | 10,447 | 501 | 5.0 | 39.7 | 40.9 | 1.2 | 3.0 |

Wholesale trade | 1,485 | 1,539 | 54 | 3.6 | 26.8 | 27.1 | .3 | 1.1 |

Retail trade | 6,772 | 6,995 | 223 | 3.3 | 46.2 | 47.0 | .8 | 1.7 |

Transportation, warehousing, and utilities | 1,690 | 1,912 | 222 | 13.1 | 34.8 | 38.5 | 3.7 | 10.6 |

Information | 732 | 743 | 11 | 1.5 | 27.3 | 27.7 | .4 | 1.5 |

Financial activities | 1,852 | 2,143 | 291 | 15.7 | 24.1 | 27.5 | 3.4 | 14.1 |

Finance and insurance | 1,180 | 1,402 | 222 | 18.8 | 20.5 | 24.0 | 3.5 | 17.1 |

Real estate and rental and leasing | 669 | 739 | 70 | 10.5 | 34.7 | 37.9 | 3.2 | 9.2 |

Professional and business services | 10,181 | 10,582 | 401 | 3.9 | 58.7 | 59.0 | .3 | .5 |

Education and health services | 5,681 | 5,997 | 316 | 5.6 | 28.6 | 29.5 | .9 | 3.1 |

Educational services | 941 | 886 | –55 | –5.8 | 29.0 | 26.5 | –2.5 | –8.6 |

Health care and social assistance | 4,741 | 5,112 | 371 | 7.8 | 28.5 | 30.1 | 1.6 | 5.6 |

Leisure and hospitality | 8,414 | 8,999 | 585 | 7.0 | 63.0 | 65.5 | 2.5 | 4.0 |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 1,445 | 1,533 | 88 | 6.1 | 75.3 | 78.0 | 2.7 | 3.6 |

Accommodations and food services | 6,970 | 7,465 | 495 | 7.1 | 61.0 | 63.4 | 2.4 | 3.9 |

Other services | 2,279 | 2,336 | 57 | 2.5 | 42.5 | 43.0 | .5 | 1.2 |

Government | 3,123 | 3,503 | 380 | 12.2 | 14.1 | 16.0 | 1.9 | 13.5 |

Federal | 332 | 353 | 21 | 6.3 | 11.6 | 12.5 | .9 | 7.8 |

State and local | 2,790 | 3,148 | 358 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 16.5 | 2.0 | 13.8 |

Notes: (1) The annual number of hires is the total number of hires during the entire year. | ||||||||

| Hires | Northeast | South | Midwest | West | ||

| Number (thousands): | ||||||

| 2011 | 8,317 | 18,899 | 11,505 | 10,954 | ||

| 2012 | 8,443 | 20,543 | 11,613 | 11,395 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | 126 | 1,644 | 108 | 441 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | 1.5 | 8.7 | .9 | 4.0 | ||

| Rate (percent): | ||||||

| 2011 | 33.3 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 38.0 | ||

| 2012 | 33.3 | 42.2 | 38.2 | 38.8 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | .0 | 2.7 | –.3 | .8 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | .0 | 6.8 | –.8 | 2.1 |

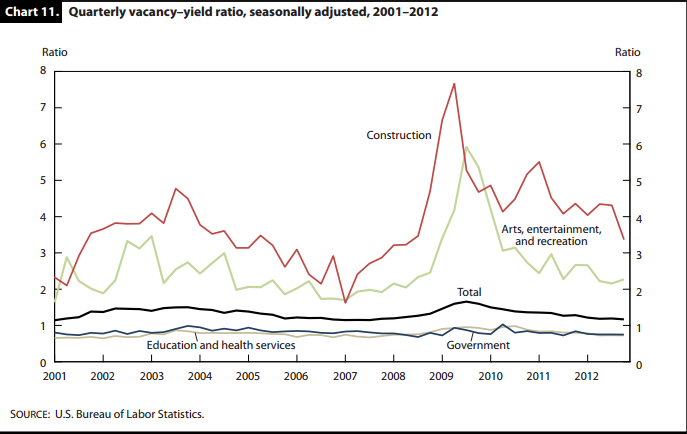

Another way to gauge potential unmet labor demand in different industries is through the stock-flow vacancy–yield ratio, the ratio of hires to job openings. This measure can provide valuable insight into the labor market over time.11 For example, in December 2012 there were 4,195,000 hires and 3,612,000 job openings, so the vacancy–yield ratio for that month and year was 1.16 (4,195,000/3,612,000).

The vacancy–yield ratios for construction and for arts, entertainment, and recreation often are the most affected by the business cycle. Because of monthly fluctuations in the data, seasonally adjusted quarterly estimates are used. In the first quarter of 2012, construction had 4.04 hires per job opening and arts, entertainment, and recreation had 2.66 hires per job opening. Both ratios decreased by the fourth quarter, to 3.38 and 2.27 hires per job opening, respectively. This trend matches the 2012 total nonfarm trend, which showed a decrease from 1.22 hires per job opening in the first quarter to 1.17 hires per job opening in the final quarter. (See chart 11.)

Separations. In 2012, the number of workers separated from their jobs, or, simply, number of separations, during the year began to increase, after having leveled off the previous year. The annual number of separations rose 4.3 percent, from 47.6 million in 2011 to 49.7 million in 2012. By contrast, in 2011 the annual number of separations held steady at its 2010 level of 47.6 million. (See table 5.) On a quarterly basis, the number of separations was up 2.1 percent in the first quarter of 2012, up 4.7 percent in the second quarter, down 3.8 percent in the third quarter, and down 0.4 percent in the final quarter. The number of separations stood at its 2012 low of 3.9 million in January and reached a yearly high of 4.4 million in May. Table 6 presents the annual number of separations and the annual rate of separations, by industry, for 2011 and 2012.

| Year | Number (thousands) | Percent change from previous year | Annual rate (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|

2001 | 64,765 | (1) | 49.1 |

2002 | 59,190 | –8.6 | 45.4 |

2003 | 56,487 | –4.6 | 43.5 |

2004 | 58,340 | 3.3 | 44.4 |

2005 | 60,733 | 4.1 | 45.4 |

2006 | 61,565 | 1.4 | 45.2 |

2007 | 61,162 | –.7 | 44.4 |

2008 | 58,627 | –4.1 | 42.9 |

2009 | 51,532 | –12.1 | 39.4 |

2010 | 47,646 | –7.5 | 36.7 |

2011 | 47,626 | .0 | 36.2 |

2012 | 49,676 | 4.3 | 37.1 |

Notes: (1) The JOLTS program did not begin until 2001, so there are no data for the previous year. | |||

| Industry | Number (thousands) | Rate (percent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | |

Total | 47,626 | 49,676 | 2,050 | 4.3 | 36.2 | 37.1 | 0.9 | 2.5 |

Total private | 44,173 | 46,152 | 1,979 | 4.5 | 40.4 | 41.3 | .9 | 2.2 |

Mining and logging | 237 | 354.0 | 117 | 49.4 | 30.1 | 41.6 | 11.5 | 38.2 |

Construction | 3,906 | 3,808 | –98 | –2.5 | 70.6 | 67.5 | –3.1 | –4.4 |

Manufacturing | 2,820 | 2,808 | –12 | –.4 | 24.0 | 23.6 | –.4 | –1.7 |

Durable goods | 1,538 | 1,659 | 121 | 7.9 | 21.1 | 22.2 | 1.1 | 5.2 |

Nondurable goods | 1,283 | 1,146 | –137 | –10.7 | 28.8 | 25.7 | –3.1 | –10.8 |

Trade, transportation, and utilities | 9,436 | 9,924 | 488 | 5.2 | 37.6 | 38.9 | 1.3 | 3.5 |

Wholesale trade | 1,365 | 1,429 | 64 | 4.7 | 24.6 | 25.2 | .6 | 2.4 |

Retail trade | 6,476 | 6,757 | 281 | 4.3 | 44.2 | 45.4 | 1.2 | 2.7 |

Transportation, warehousing, and utilities | 1,598 | 1,739 | 141 | 8.8 | 32.9 | 35.0 | 2.1 | 6.4 |

Information | 727 | 749 | 22 | 3.0 | 27.2 | 28.0 | .8 | 2.9 |

Financial activities | 1,815 | 2,043 | 228 | 12.6 | 23.6 | 26.2 | 2.6 | 11.0 |

Finance and insurance | 1,147 | 1,322 | 175 | 15.3 | 19.9 | 22.7 | 2.8 | 14.1 |

Real estate and rental and leasing | 669 | 721 | 52 | 7.8 | 34.7 | 36.9 | 2.2 | 6.3 |

Professional and business services | 9,616 | 10,004 | 388 | 4.0 | 55.5 | 55.8 | .3 | .5 |

Education and health services | 5,269 | 5,578 | 309 | 5.9 | 26.5 | 27.5 | 1.0 | 3.8 |

Educational services | 810 | 841 | 31 | 3.8 | 24.9 | 25.1 | .2 | .8 |

Health care and social assistance | 4,459 | 4,740 | 281 | 6.3 | 26.8 | 27.9 | 1.1 | 4.1 |

Leisure and hospitality | 8,117 | 8,616 | 499 | 6.1 | 60.8 | 62.7 | 1.9 | 3.1 |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 1,472 | 1,450 | –22 | –1.5 | 76.7 | 73.8 | –2.9 | –3.8 |

Accommodations and food services | 6,643 | 7,163 | 520 | 7.8 | 58.1 | 60.8 | 2.7 | 4.6 |

Other services | 2,228 | 2,268 | 40 | 1.8 | 41.6 | 41.7 | .1 | .2 |

Government | 3,453 | 3,525 | 72 | 2.1 | 15.6 | 16.1 | .5 | 3.2 |

Federal | 370 | 389 | 19 | 5.1 | 12.9 | 13.8 | .9 | 7.0 |

State and local | 3,083 | 3,135 | 52 | 1.7 | 16.0 | 16.4 | .4 | 2.5 |

Notes: (1) The annual number of separations is the total number of separations during the entire year. | ||||||||

After the end of the recession, the number of separations trended downward, from 4.2 million in June 2009 to a trough of 3.7 million in April 2011. Since then, the number of separations has increased steadily, reaching 4.1 million by the end of 2012. The main driver of the increase was a rise in the number of quits. (See chart 8.) The number of separations has yet to reach the level of 5.0 million at which it stood at the beginning of the recession, in December 2007.

1. Quits. The total number of people quitting their jobs, or, simply, number of quits, during the year has increased for the past 3 years. The annual number of quits increased 7.8 percent from 2011 to 2012, rising from 23.3 million to 25.1 million. By way of comparison, it had increased 6.1 percent from 2010 to 2011. The following tabulation gives level, percent change, and rate statistics (not seasonally adjusted) on quits over the 2-year span:

| Year | Number of quits (thousands) | Percent change from previous year | Rate of quits (percent) | |||

| 2010 | 21,978 | 4.5 | 16.9 | |||

| 2011 | 23,313 | 6.1 | 17.7 | |||

| 2012 | 25,132 | 7.8 | 18.8 |

On a quarterly basis, the number of quits rose 4.9 percent in the first quarter of 2012, fell 2.5 percent in the second quarter and another 2.7 percent in the third quarter, and grew 2.2 percent in the final quarter. The number of quits stood at its 2012 low of 2.0 million in January and reached a yearly high of 2.2 million in March.

Since the end of the recession, the number of quits has been trending upward, from 1.7 million in June 2009 to 2.1 million in December 2012. Still, it has yet to reach its level of 2.9 million at the beginning of the recession, in December 2007.

Table 7 shows the annual number of quits and the annual rate of quits, by industry, for 2011 and 2012. The annual rate of total nonfarm quits increased from 17.7 percent in 2011 to 18.8 percent in 2012. The annual quits rate declined in only two industries: nondurable goods manufacturing, where it fell by 5.1 percent, from 13.7 percent in 2011 to 13.0 percent in 2012; and arts, entertainment, and recreation, in which it dropped by 0.7 percent, from 26.7 percent in 2011 to 26.5 percent in 2012. In 2012, the industries with the largest growth in annual quits rates were mining and logging, where the rate rose 32. 9 percent, from 17.3 percent in 2011 to 23.0 percent in 2012, and the federal government, which saw an increase of 20.5 percent, from 3.9 percent in 2011 to 4.7 percent in 2012.

| Industry | Number (thousands) | Rate (percent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | 2011 | 2012 | Change | Percent change | |

Total | 23,313 | 25,132 | 1,819 | 7.8 | 17.7 | 18.8 | 1.1 | 6.2 |

Total private | 21,905 | 23,589 | 1,684 | 7.7 | 20.0 | 21.1 | 1.1 | 5.5 |

Mining and logging | 136 | 196.0 | 60 | 44.1 | 17.3 | 23.0 | 5.7 | 32.9 |

Construction | 924 | 946 | 22 | 2.4 | 16.7 | 16.8 | .1 | .6 |

Manufacturing | 1,247 | 1,284 | 37 | 3.0 | 10.6 | 10.8 | .2 | 1.9 |

Durable goods | 637 | 706 | 69 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 9.5 | .7 | 8.0 |

Nondurable goods | 612 | 579 | –33 | –5.4 | 13.7 | 13.0 | –.7 | –5.1 |

Trade, transportation, and utilities | 5,170 | 5,530 | 360 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 21.7 | 1.1 | 5.3 |

Wholesale trade | 614 | 688 | 74 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 9.0 |

Retail trade | 3,826 | 3,984 | 158 | 4.1 | 26.1 | 26.8 | .7 | 2.7 |

Transportation, warehousing, and utilities | 729 | 855 | 126 | 17.3 | 15.0 | 17.2 | 2.2 | 14.7 |

Information | 389 | 431 | 42 | 10.8 | 14.5 | 16.1 | 1.6 | 11.0 |

Financial activities | 967 | 1,065 | 98 | 10.1 | 12.6 | 13.7 | 1.1 | 8.7 |

Finance and insurance | 644 | 694 | 50 | 7.8 | 11.2 | 11.9 | .7 | 6.3 |

Real estate and rental and leasing | 325 | 371 | 46 | 14.2 | 16.9 | 19.0 | 2.1 | 12.4 |

Professional and business services | 4,421 | 4,622 | 201 | 4.5 | 25.5 | 25.8 | .3 | 1.2 |

Education and health services | 2,910 | 3,203 | 293 | 10.1 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 1.2 | 8.2 |

Educational services | 373 | 395 | 22 | 5.9 | 11.5 | 11.8 | .3 | 2.6 |

Health care and social assistance | 2,536 | 2,808 | 272 | 10.7 | 15.2 | 16.5 | 1.3 | 8.6 |

Leisure and hospitality | 4,722 | 5,196 | 474 | 10.0 | 35.4 | 37.8 | 2.4 | 6.8 |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 513 | 521 | 8 | 1.6 | 26.7 | 26.5 | –.2 | –.7 |

Accommodations and food services | 4,209 | 4,678 | 469 | 11.1 | 36.8 | 39.7 | 2.9 | 7.9 |

Other services | 1,013 | 1,114 | 101 | 10.0 | 18.9 | 20.5 | 1.6 | 8.5 |

Government | 1,406 | 1,543 | 137 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 7.0 | .6 | 9.4 |

Federal | 111 | 131 | 20 | 18.0 | 3.9 | 4.7 | .8 | 20.5 |

State and local | 1,295 | 1,413 | 118 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 7.4 | .7 | 10.4 |

Notes: (1) The annual number of quits is the total number of quits during the entire year. | ||||||||

| Quits | Northeast | South | Midwest | West | ||

| Number (thousands): | ||||||

| 2011 | 3,349 | 9,396 | 5,447 | 5,121 | ||

| 2012 | 3,669 | 10,588 | 5,579 | 5,296 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | 320 | 1,192 | 132 | 175 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | 9.6 | 12.7 | 2.4 | 3.4 | ||

| Rate (percent): | ||||||

| 2011 | 13.4 | 19.7 | 18.2 | 17.7 | ||

| 2012 | 14.5 | 21.8 | 18.4 | 18.0 | ||

| Change, 2011–2012 | 1.1 | 2.1 | .2 | .3 | ||

| Percent change, 2011–2012 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

JOLTS DATA SHOW THAT, WHILE LABOR DEMAND, as measured by the number of job openings, increased during 2012, worker flow, in the form of an increase in hires and separations, has been slower to improve. Nevertheless, layoffs and discharges, as well as other separations, have returned to prerecession levels, adding stability to the growth of the labor market as fewer employees are involuntarily separated from their jobs and employees begin to feel more comfortable about retiring again.

Kendra C. Hathaway, "Job openings continue to grow in 2012, hires and separations less so," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2013

1 The term “industry” can refer to a supersector, sector, or subsector, depending on the context. In analyzing industries, the JOLTS program follows the North American Industrial Classification System.

2 The most detailed geographical breakout the jolts sample can provide is by region: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West.

3 For data on employment, see “Current Employment Statistics—CES (National)” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, published monthly), https://www.bls.gov/ces.

4 Richard L. Clayton, James R. Spletzer, and John C. Wohlford, “Conference Report: JOLTS Symposium,” Monthly Labor Review, February 2011, pp. 41–47, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2011/02/art4full.pdf, especially p. 44.

5 “U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions” (National Bureau of Economic Research), https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions.

6 The U.S. Census Bureau defines the four regions of the United States as follows: Northeast—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont; South—Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia; Midwest—Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin; West—Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming. This listing applies to all tabulations that follow showing estimates for the U.S. regions.

7 For data on unemployment, see “Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, published monthly), https://www.bls.gov/cps.

8 See, for example, Ed Crooks, “German giant says U.S. workers lack skills,” Europe News (CNBC, June 20, 2011), https://www.cnbc.com/id/43459947; and Rand Ghayad and William Dickens, “It’s not a skill mismatch: disaggregate evidence on the U.S. unemployment–vacancy relationship,” VOX, Jan. 5, 2013, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/its-not-skill-mismatch-disaggregate-evidence-us-unemployment-vacancy-relationship.

9 For data on local area unemployment, see “Local Area Unemployment Statistics” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/lau.

10 For a discussion of hires, separations, and their procyclicality, see Caryn N. Bruyere, Guy L. Podgornik, and James R. Spletzer, “Employment dynamics over the last decade,” Monthly Labor Review, August 2011, pp. 16–29, especially p. 23, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2011/08/art2full.pdf.

11 Regis Barnichon, Michael Elsby, Bart Hobijn, and Ayşegűl Şahin, “Which industries are shifting the Beveridge curve?” Monthly Labor Review, June 2012, pp. 25–37, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2012/06/art2full.pdf.

12 See “Consumer Confidence Survey®: the Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index® improves in April” (The Conference Board, Apr. 30, 2013), https://www.conference-board.org/data/consumerconfidence.cfm. The index measures consumers’ attitudes about the economy, as indicated by their levels of spending and saving.

13 See, for example, Emily Brandon, “Planning to retire: most baby boomers plan to delay retirement,” U.S. News, June 30, 2010, https://money.usnews.com/money/blogs/planning-to-retire/2010/06/30/most-baby-boomers-plan-to-delay-retirement.